A quick letter from the team

In many ways, 2020 is the year most of us would rather not look back upon, but for once it’s not hyperbole to say that this has been one for the history books. Great disruptions of the kind wrought by the COVID-19 virus occur infrequently, but when they do they tend to mark the end of eras and open the way for genuine social and political reform. This year our small team at Per Capita has shown that we can be drivers of that kind of reform and that our supporters can be sure the impact of every dollar donated to us is maximised. If you’d like to support our work, sign up to become a monthly supporter here:

We’ve worked hard this year to push against the “snap back” to what came before, and to argue for a better future on the other side of the pandemic. With more than 20 individual policy papers and submissions to public inquiries, a book of essays and more than a dozen Per Capita online events throughout the year, 2020 has been a busy and productive year for our small team. And that’s not to mention more than 1,000 media mentions and appearances including print, television, and radio interviews, quotes and backgrounding for news articles, opinion and comment pieces, and coverage of our reports, events, and other work. A quick look back at what we achieved in this most remarkable of years is below.

As we look ahead to 2021, our work will become even more important. In what is likely to be an election year, the need for evidence-based policy development and advocacy for a progressive, inclusive and sustainable policy agenda to lead Australia’s recovery is greater than ever. The coming months will be critical in determining what kind of future we will leave to our kids and grandchildren. Will they have the same opportunities to build a good life in a safe and secure country as previous generations of Australians have had? Or will we consign them to a life if struggle and insecurity, with low quality jobs, an impoverished public sphere, poor quality public services and an increasingly uninhabitable planet?

Per Capita’s agenda for 2021 is just as bold and brave as was 2020’s. With upcoming work on the return to a full employment economy through reform of our macro- and micro-economic thinking, investment in the foundational economy, rethinking aged care, more work on housing security and employment services reform, and a big focus on building the jobs of the future, we will continue to devote our energy and passion to creating a vision for a stronger, fairer, more sustainable Australia, with the wellbeing of people and planet at its core.

We can’t do this without you. If you haven’t already, please consider becoming a supporter of Per Capita. A regular monthly donation of as little as $10 (tax deductible) will make a great difference to small team of dedicated people. We need your support to take on the well-funded think tanks and cheerleaders for extreme market capitalism, who have done so much to break the bonds of community and have continued, during this extraordinary year, to put profits ahead of people.

Thank you for your ongoing interest in, and support for, our work. At the end of 2020, we hope you and your loved ones are safe and well, and looking forward, as we are, to what happens next.

Happy holidays to all our supporters,

The team at Per Capita – Emma, Abigail, Shirley, Matt, Simone, and John.

Per Capita’s Year in Review

We kicked off 2020 with a couple of major submissions to public inquiries: the Inquiry into Homelessness in Victoria (which was followed in July by a submission to the Inquiry into Homelessness in Australia) and the Retirement Income Review (RIR).

Our submissions to the two homelessness inquiries argued for a significant boost to investment in social housing – particularly public housing – at both the state and federal level. We urged both committees to recognise that high quality public housing, built to universal design standards in appropriate locations, and combined with holistic support, would be far and away the best way to address the twin crises of homelessness and housing insecurity in both Victoria and Australia. We were very happy to see the Victorian government announce the most significant single investment in social housing in the state’s history at its most recent budget; unfortunately, we are yet to see investment from the Commonwealth.

Our submission to the RIR was based on our many years of work in the Centre for Applied Policy in Positive Ageing (CAPPA) and emphasised the fundamental role played by home ownership in retirement. With outright home-ownership increasingly out of reach, we argued for a significant re-think of the retirement income system, and for real reform of the tax concessions that go to high-income earners and wealthy Australians through the superannuation system and housing investment market. The government largesse bestowed on our investor class should be redirected to support the most vulnerable retirees, too many of whom are single women trapped in the private rental market and living in poverty in their old age. The provision of secure housing and care support for old-age pensioners should be the focus of reform – and that shouldn’t come at the expense of individual retirement savings, as some in the government are now suggesting.

Sadly, it looks like the only major reform being considered by the government after the RIR handed down its report is to limit or abolish universal superannuation. Having predicted this while engaged in the debate around the RIR, we followed our submission with a look at the arguments being made by some in the government to again freeze the rate of the superannuation guarantee. In February, we released The Super Freeze: What You’ve Lost, which showed that as a result of the freeze on the SG rate legislated by the Abbott Government in 2014, the average worker has lost $4332.99 in super over the intervening five years, while at the same time, their take-home pay has declined by $1092.00 in real terms, giving them a net loss of $5424.99.

Sadly, it looks like the only major reform being considered by the government after the RIR handed down its report is to limit or abolish universal superannuation. Having predicted this while engaged in the debate around the RIR, we followed our submission with a look at the arguments being made by some in the government to again freeze the rate of the superannuation guarantee. In February, we released The Super Freeze: What You’ve Lost, which showed that as a result of the freeze on the SG rate legislated by the Abbott Government in 2014, the average worker has lost $4332.99 in super over the intervening five years, while at the same time, their take-home pay has declined by $1092.00 in real terms, giving them a net loss of $5424.99.

This report, by Emma Dawson and Shirley Jackson, was accompanied by an online calculator that enabled people to calculate their own losses in super and income since 2014. As the campaign against lifting the SG rate to 12% again gathers pace, this work – which shows the actual, rather than theoretical, result of holding down superannuation payments for workers – remains vitally important.

Keeping our focus on the importance of home as we age, February also saw the launch of our policy brief series, in partnership with The Australian Centre for Social Innovation, Home for Good. So much more than mere shelter from the elements, the concept of home encompasses all that provides us with a place in the world: it underpins our identity; our relationships with one another; our understanding of who we are and where we fit in the greater scheme of things. Yet this notion of home is all too often overlooked when it comes to the role of the home in modern society, and to the development of policies that support the provision of housing and the sustenance of life.

This important series of policy briefs is intended to restore the idea of home as both a psychological and social asset, rather than just a financial asset, to our discourse on housing. Drawing on years of practice by TACSI and Per Capita’s substantial research in the field of positive ageing, Myfan Jordan, supported by Emma Dawson and Abigail Lewis, set out to demonstrate that by recognising the role and particular importance of home as people age, we can craft public policy responses that more fully address the needs of all Australians.

The series included three discussion papers that grappled with different policy challenges:

- Improving the Private Rental Market for Older Australians, released in March;

- Social Housing for an Ageing Population, released in May; and

- Communities for Wellbeing, released in July.

Given the renewed focus by state governments and the federal opposition on the provision of secure and affordable housing in the wake of COVID-19, we will continue to work with our friends at TACSI to promote policies that will provide homes that meet the needs of all Australians and work towards eliminating homelessness and housing insecurity across the nation.

March saw the launch of our landmark report on Gender Equality in Australia. Measure for Measure brought together, for the first time, an overview of the evidence of the way gender-based discrimination and disadvantage accumulate over the life course for Australian women with an analysis of its causes and recommendations for change; and makes the case for a national, bi-partisan commitment to measure, evaluate and take action to close the gender equality gap in Australia.

March saw the launch of our landmark report on Gender Equality in Australia. Measure for Measure brought together, for the first time, an overview of the evidence of the way gender-based discrimination and disadvantage accumulate over the life course for Australian women with an analysis of its causes and recommendations for change; and makes the case for a national, bi-partisan commitment to measure, evaluate and take action to close the gender equality gap in Australia.

This important report, authored by Emma Dawson, Tanja Kovac and Abigail Lewis, revealed that, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index, Australia has dropped from a ranking of 15th in the world when the index commenced to 44th in 2020 – a decline of 29 places in just 14 years. Most countries that are now out-performing Australia on the GGGI produce an annual review of national performance against gender equality targets. They also have gender budget units in their treasury, as well as gender architecture and appropriate levels of funding to monitor performance and drive innovation. The reality is that, without monitoring and action, Australia’s gender equality performance will continue to decline.

This report is intended to provide the foundation for a long-term project to produce a national, comprehensive longitudinal study of the progress towards gender equality in Australia. We hope to release the second report in this annual series later in 2021.

By the end of March 2020, of course, everything had changed. Our Executive Director, Emma Dawson, was quick to recognise the epoch-defining nature of the crisis, and to call for a national commitment to rebuild a better society on the other side of the pandemic. Her letter to friends of Per Capita on 25 March was written during our second week of working from home during Victoria’s first lock-down, and predicted that COVID-19 would result in a world-wide economic downturn unseen since the Great Depression.

Emma wrote that, just as individuals living with complex health conditions are at greater risk from COVID-19, our 21st century Western civilisation was beset by economic and social co-morbidities that left us dangerously exposed to the impact of a crisis outside of our control. The decades-long project to let free markets dictate our way of life has left societies riven with income and wealth inequality, insecure work, a deliberately degraded welfare state, and shrivelled pubic services, she said. We are overly dependent for our wellbeing on powerful multinational corporations that routinely practice price gouging, wage theft and asset stripping, with no regard for the sustainability of the planet or the living standards of ordinary people.

Emma’s diagnosis was that capitalism is broken, and our response to this massive disruption may well be our last, best chance fix it: to reshape our economy to serve the wellbeing of people and the planet. This letter, and the policy thinking that lay behind it, was the genesis of the book Emma was to co-edit with Professor Janet McCalman, released later in the year.

By the time of the letter’s release, the impact of the greatest health crisis in a century was upending politics and public life, and the most obvious and immediate change was to the conversation about government spending and public debt. After years of railing against the surplus fetish of successive Australian governments, we seized the opportunity in April to put out Some Facts About Debt, a discussion paper by Emma Dawson and Matt Lloyd- Cape, that exploded the pernicious myth that government debt is like household debt.

By the time of the letter’s release, the impact of the greatest health crisis in a century was upending politics and public life, and the most obvious and immediate change was to the conversation about government spending and public debt. After years of railing against the surplus fetish of successive Australian governments, we seized the opportunity in April to put out Some Facts About Debt, a discussion paper by Emma Dawson and Matt Lloyd- Cape, that exploded the pernicious myth that government debt is like household debt.

We made what should be an obvious point but one that has been lost in the endless pursuit of a balanced budget: that the national economy is not an end in itself, but a means by which to exchange goods and services, and distribute prosperity to ensure the wellbeing of a nation’s people.

As we begin to emerge from this health and economic emergency, there is likely to be a fierce battle waged over how we restore economic activity and recover from the massive loss of jobs and income. On one side will be a push to return to the kind of economic activity that has exacerbated wealth and income inequality, and led to the crisis of anthropogenic climate change that threatens to end life as we know it. On the other is an opportunity to reset society to be more sustainable, equitable and enjoyable for all of us, and to pay down the debt we have taken on to protect jobs and livelihoods through this crisis without causing further damage to Australians through the imposition of austere cuts to services and incomes. This widely read paper fuelled the debate about the sort of country we want to be after the pandemic, and set the scene for much of our work for the rest of 2020.

Later in April, we kicked off a series of discussion papers on employment services reform, with Redesigning Employment Services after COVID-19, in which Simone Casey argued that neither the existing jobactive system, nor the Government’s New Employment Services model, are a good fit for the post COVID-19 unemployment scenario. Both models are hamstrung by a dependency on job outcome payments, which leads to under-investment in the needs of people most at risk of long-term unemployment. The paper made the case for undertaking an urgent review of employment services to ensure that those left without work after COVID-19 are offered support services that meet their needs and maximise their chances to find good, secure jobs.

Later in April, we kicked off a series of discussion papers on employment services reform, with Redesigning Employment Services after COVID-19, in which Simone Casey argued that neither the existing jobactive system, nor the Government’s New Employment Services model, are a good fit for the post COVID-19 unemployment scenario. Both models are hamstrung by a dependency on job outcome payments, which leads to under-investment in the needs of people most at risk of long-term unemployment. The paper made the case for undertaking an urgent review of employment services to ensure that those left without work after COVID-19 are offered support services that meet their needs and maximise their chances to find good, secure jobs.

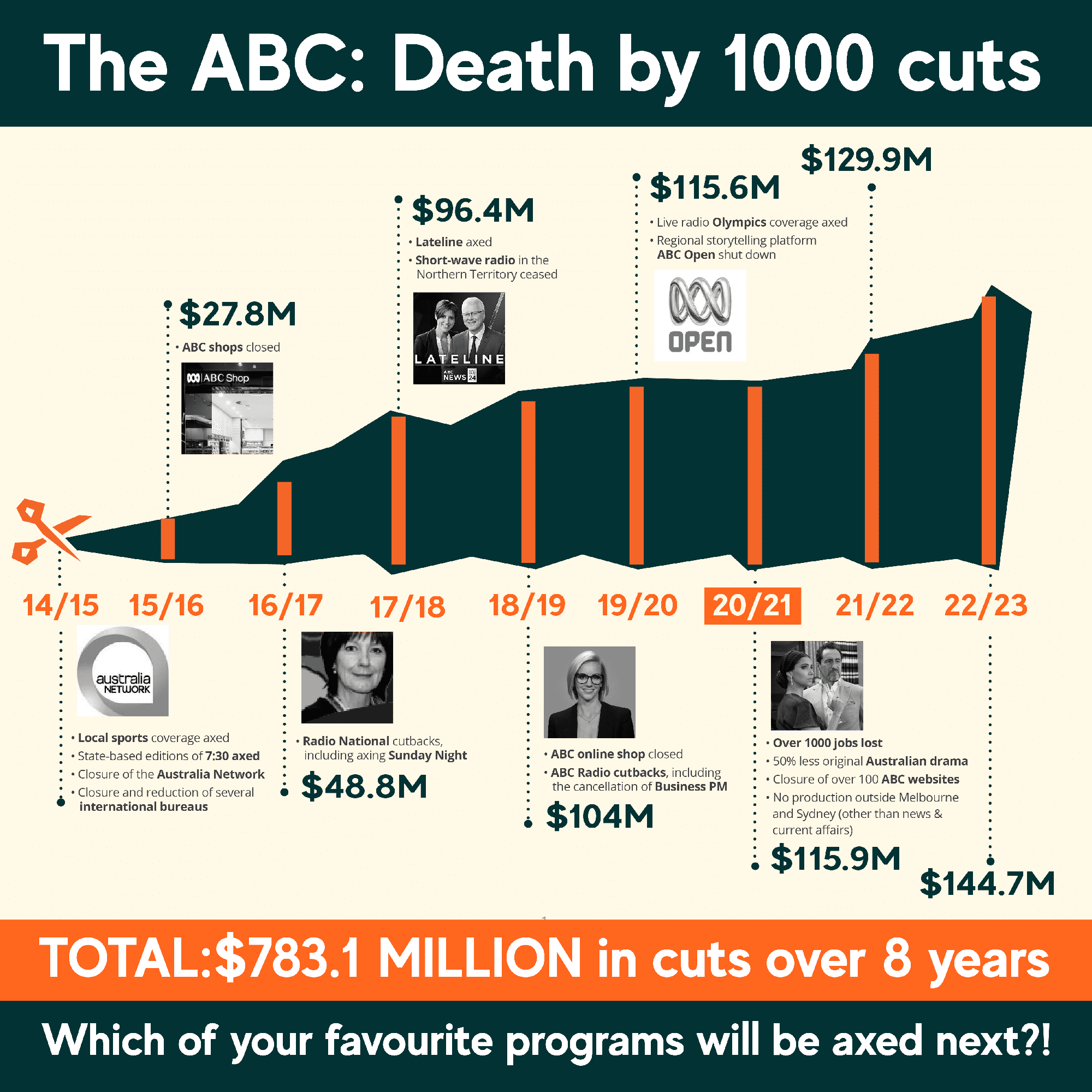

Early May saw the release of a research report Emma Dawson produced for GetUp! into the funding cuts imposed on the ABC since the Coalition Government came to office. It’s Our ABC uncovered details of a virtually unprecedented attack on the operational capability of Australia’s national broadcaster and found that, by 2022, the end of the third triennial funding period during which the Coalition Government has been in power, the total funding cut from the ABC will be over $783 million. Despite claims to the contrary by the Prime Minister following the release of the report, the fact is that the national broadcaster’s 2019-20 operational revenue from Government of $879 million represents a decrease in real funding of $367 million per annum, or 29.5%, since 1985-86.

To mark the 75th anniversary of the Curtin Government’s White Paper on Full Employment, we held an online symposium featuring ALP President Wayne Swan, current Labor MPs Andrew Leigh and Ged Kearney, and ACTU President Michele O’Neil to discuss the framework needed for a full employment economy in a post-carbon Australia. This event, which replaced the conference we had planned for Canberra, brought together more than 300 people to engage in a thoughtful conversation about the need to reinstate full employment as the first goal and responsibility of government. Much of the work outlined at this event continues to underpin Per Capita’s approach to policy development, both in 2020 and beyond.

May also saw the release of Slack in the System: The Economic Cost of Underemployment, a discussion paper from Matt Lloyd-Cape that found that, in the first weeks of the pandemic, there was a steep rise in underemployment: the month-on-month increase to April was 50%, or over 600,000 people. By May, just under 15% of the Australian workforce was underemployed. Combined with the unemployment rate, Australia had a labour force under-utilisation rate of 19.9% – meaning one in five Australians did not have sufficient work to support themselves and their families. This paper puts these new statistics in perspective, noting that well before the arrival of COVID-19, the significant slack in the Australian labour market was suppressing wages and productivity, and leading to a crisis of insecure work.

This was followed in June by Shirley Jackson’s Coming of Age in a Crisis: Young Workers, COVID and the Youth Guarantee, which found that, at the height of the national health crisis, almost two out of three young workers didn’t have enough work to meet their needs.

Shirley argued for a bold new approach to tackling youth unemployment and insecure work, with policy reform in the areas of employment services, education and training, active labour market programs, social procurement, apprenticeships and graduate employment programs. Perhaps predicting the limitations of the government’s eventual intervention with the “JobMaker” wage subsidy program, Shirley urged us to think beyond providing entry-level, minimum wage jobs to cut youth unemployment numbers, and implement a comprehensive suite of policies to create a genuine Youth Guarantee, under which young Australians are supported to achieve their full potential and to realise the promise of Australia that has been afforded to previous generations.

This concept is being developed through a co-design project with young people in Melbourne’s outer west, generously supported by the Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation, which is investigating the necessary elements for an appropriate Youth Guarantee for Australia in the post-COVID world. The first reports from this project will be published early in 2021.

Following this look at the fortunes of young Australians in a brutal labour market, Simone Casey’s second discussion paper on employment services reform later in June argued that we cannot return to the same system of “mutual obligation” for those seeking work that was in place before the pandemic. Mutual Obligation after COVID-19: the Work-For-The-Dole Timebomb looked at the likely explosion in cost for current mutual obligation programs, and compared this to the very low rate of return they offer to unemployed people. Simone’s key recommendation was that Work for the Dole be replaced with a genuine work experience program for people experiencing long term unemployment, which could be established through community economic regeneration grants for job creation projects across Australia.

Following this look at the fortunes of young Australians in a brutal labour market, Simone Casey’s second discussion paper on employment services reform later in June argued that we cannot return to the same system of “mutual obligation” for those seeking work that was in place before the pandemic. Mutual Obligation after COVID-19: the Work-For-The-Dole Timebomb looked at the likely explosion in cost for current mutual obligation programs, and compared this to the very low rate of return they offer to unemployed people. Simone’s key recommendation was that Work for the Dole be replaced with a genuine work experience program for people experiencing long term unemployment, which could be established through community economic regeneration grants for job creation projects across Australia.

July saw the release of a discussion paper by Emma Dawson, Abigail Lewis and Matt Lloyd-Cape on The Future of Australia Post, produced for the Communications, Electrical and Plumbing Union, which argued that the federal government should be expanding the trusted services of Australia Post in the interests of the Australian people and to strengthen the revenue base and viability of the enterprise.

This was followed later in the month by a detailed policy paper, authored by Warwick Smith with support from Abigail Lewis and Emma Dawson, that made the case for establishing a public bank within Australia Post. PostBank: Filling a Void, Securing Essential Services argued that the establishment of a postal banking service operating within the existing infrastructure footprint of Australia Post outlets nation-wide could provide banking services to Australians who are currently underserviced by the existing banking sector, while ensuring the continuation of postal services in remote and regional communities, and underpinning the ongoing viability of Australia Post’s services across Australia. Moreover, with a social benefit mandate, PostBank could also improve banking services across the country by setting new standards for financial products and services that other banks will have to meet if they are to compete.

August saw the release of The Herstory of Superannuation, a report written by Emma Dawson and Simone Casey for Women In Super, which looked at the history of superannuation for Australian women, marked its progress towards equity, and identified what more could to be done to improve the system in order to mitigate women’s vulnerability to poverty in retirement. The report found that the creation of universal superannuation by the Keating Government was the single biggest factor in improving retirement outcomes for Australian women since Federation, but that, even so, the design of universal superannuation, primarily its flat tax structure and its indifference to the nature of women’s labour force participation, as well as a number of policy interventions in the years since its introduction that have deliberately favoured higher-income men, means that too many Australian women will not accrue sufficient savings for a secure retirement. The report offers some recommendations for addressing gender inequity in retirement incomes.

August saw the release of The Herstory of Superannuation, a report written by Emma Dawson and Simone Casey for Women In Super, which looked at the history of superannuation for Australian women, marked its progress towards equity, and identified what more could to be done to improve the system in order to mitigate women’s vulnerability to poverty in retirement. The report found that the creation of universal superannuation by the Keating Government was the single biggest factor in improving retirement outcomes for Australian women since Federation, but that, even so, the design of universal superannuation, primarily its flat tax structure and its indifference to the nature of women’s labour force participation, as well as a number of policy interventions in the years since its introduction that have deliberately favoured higher-income men, means that too many Australian women will not accrue sufficient savings for a secure retirement. The report offers some recommendations for addressing gender inequity in retirement incomes.

In September, we released the 2020 Per Capita Tax Survey. Again generously supported by David Morawetz’s Social Justice Fund, the tenth edition of this annual poll was, for the first time, conducted twice in one year: the first time in February, before the onset of COVID-19 in Australia, and the second six months later, in August, as the impact of the pandemic was becoming clear.

The results were striking. In the wake of the biggest health and economic crisis in a century, Australians demonstrated a renewed appreciation of the essential services provided through our system of government: scores for the value, accessibility, quality and usefulness of public services all showed notable increases between February and August. Public approval of the use of government debt to underpin long-term investment was also significantly higher in August compared to previous surveys, with a remarkable 15 point increase in support over the six months since the February poll. And despite the record outlays of recent months, a majority of respondents still want to see governments spend more on health, education and social security.

The results were striking. In the wake of the biggest health and economic crisis in a century, Australians demonstrated a renewed appreciation of the essential services provided through our system of government: scores for the value, accessibility, quality and usefulness of public services all showed notable increases between February and August. Public approval of the use of government debt to underpin long-term investment was also significantly higher in August compared to previous surveys, with a remarkable 15 point increase in support over the six months since the February poll. And despite the record outlays of recent months, a majority of respondents still want to see governments spend more on health, education and social security.

Support for a significant, permanent increase in the rate of JobSeeker was, by August, significantly higher than it was pre-pandemic, while the level of support for the government’s Stage 3 tax cuts, was weak, with only 13% of respondenst supporting the current distribution of the tax cuts, which overwhelmingly favours high income earners.

Later in September came Simone Casey’s third paper in the series analysing the operation of employment services. At What Cost? Getting Back to JobActive provided an update on earlier estimates of the cost of jobactive given the significant increase in the number of unemployed people needing assistance, and reflected on how the system had adapted to the unforeseen surge in case numbers during the recession.

Simone found that there is likely to be substantial inflation in the cost of jobactive, necessitating the allocation of additional government funding for employment services, unless there are radical changes to the jobactive model, and offered a number of policy recommendations that would strengthen the capacity of the system to provide useful support for Australians seeking to return to the labour force after the widespread loss of work since early 2020.

Simone found that there is likely to be substantial inflation in the cost of jobactive, necessitating the allocation of additional government funding for employment services, unless there are radical changes to the jobactive model, and offered a number of policy recommendations that would strengthen the capacity of the system to provide useful support for Australians seeking to return to the labour force after the widespread loss of work since early 2020.

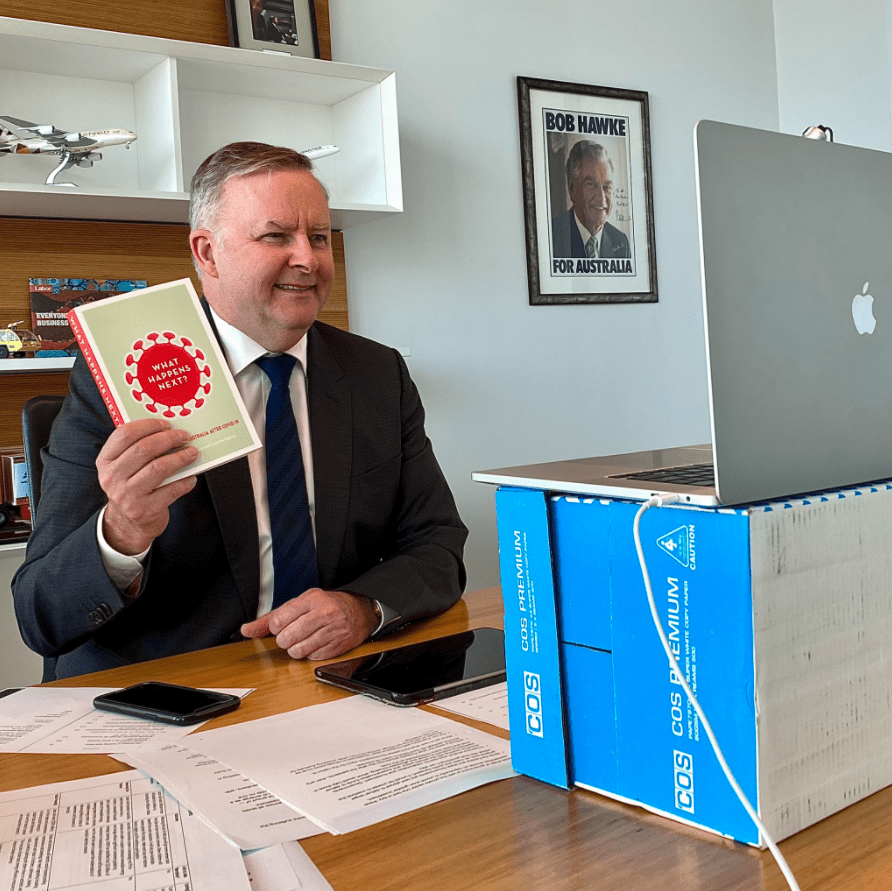

On 29 September, Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese launched What Happens Next? Reconstructing Australia After COVID-19. Co-edited by Emma Dawson and Professor Janet McCalman, this collection of essays by some of Australia’s most respected academics and policy thinkers set out a bold, progressive reform agenda to tackle the twin crises of climate change and inequality.

Featuring contributions from Per Capita fellows John Falzon, Osmond Chiu, Julie Connolly and Shireen Morris, the book brought together leading thinkers including Thomas Mayor, John Langmore, Jenny Macklin, Fiona Stanley, Jay Weatherill, Roy Green, Michele O’Neil, Elizabeth Hartnell-Young, Lachlan McCall, Stephen Parker, Rob Moodie, Mike Daube, Andrew Petersen, Emma Germano, Liz Allen, Clinton Fernandes and Peter Lewis. Chapters from some of the Opposition’s leading policy brains, including Anthony Albanese, Jim Chalmers, Terri Butler, Andrew Leigh, Clare O’Neil and Mark Butler contributed to a framework through which our collective effort can be devoted to improving the lives of all Australians in the wake of the pandemic, and to ensuring the sustainability of the world in which we live.

October saw the release of Emma Dawson’s discussion paper, The Case for a Care-led Recovery. Building on her chapter in What Happens Next?, Emma set out a clear case for increased government investment in the care economy, to create jobs for women, to improve the pay and conditions of essential care workers already in the system, and to improve the quality, affordability and accessibility of care for all Australians.

Again Emma argued that, as we rebuild our economy in the wake of COVID-19, we have the opportunity to fix broken systems, and to rethink what we value as a society, and what kind of country we want to be. Rather than a gas-fired recovery, this paper argued for a care-led recovery, in which we focus on the things that really matter to Australians: the health and wellbeing of their families and communities, the time they have to spend with one another, the security of their work and the recognition of the value we find in caring for one another. We need a new social compact for Australia, centred on the concept of care: care for each other, care for our communities, care for our environment, care for our future.

Again Emma argued that, as we rebuild our economy in the wake of COVID-19, we have the opportunity to fix broken systems, and to rethink what we value as a society, and what kind of country we want to be. Rather than a gas-fired recovery, this paper argued for a care-led recovery, in which we focus on the things that really matter to Australians: the health and wellbeing of their families and communities, the time they have to spend with one another, the security of their work and the recognition of the value we find in caring for one another. We need a new social compact for Australia, centred on the concept of care: care for each other, care for our communities, care for our environment, care for our future.

Later in October, in a paper for Together Queensland, Matt Lloyd-Cape and Shirley Jackson looked at mechanisms for improving the equity and efficiency of stimulus spending. Austerity or Prosperity? Policy Options for Resilience and Recovery argued that state and federal governments should put “gender on the tender” for public construction contracts to increase gender equity and productivity, and create easy entry retraining schemes, for roles such as teaching assistants and allied health professionals, to provide workers with quick access to socially beneficial employment. Critically, ahead of the Queensland State Election, Matt and Shirley found that the consequences of the LNP’s plan to balance the budget within four years would be disastrous, increasing unemployment in Queensland by 2.47 per cent to a rate of 9.97, a rate not seen in thirty years, and reducing gross state product (GSP) by 1.72 per cent over two years.

November saw the release of the third annual Evidence-Based Policy Analysis Project. Authored by Abigail Lewis and Per Capita’s 2020 intern Simone McKenna, the report once again scored 20 federal and state policies against Professor Kenneth Wiltshire’s criteria. The wooden spoon was awarded to the federal government’s repeal of Medevac – with no evidence of need presented, no public interest argument made, no alternative policy options considered, and only one submission in support (from the Department of Home Affairs). Top marks went to the process behind MyHealthRecord – with ten years of research, consultation, testing, and evaluation behind it, across multiple governments.

Our final policy publication for the year, in December, was a call for a Social Guarantee. In We’ve Got Your Back: Building a Framework that Protects us from Precarity, John Falzon expanded on his chapter for What Happens Next? to make a powerful argument to overturn the way we think about social security.

Our final policy publication for the year, in December, was a call for a Social Guarantee. In We’ve Got Your Back: Building a Framework that Protects us from Precarity, John Falzon expanded on his chapter for What Happens Next? to make a powerful argument to overturn the way we think about social security.

The idea of a social guarantee deliberately acknowledges that we all need help and support in our lives: we have all experienced, not only in infancy and childhood, but also as adults, the need for support from others at key moments in our lives, be it professional health support, emotional support, financial support, or some other form of help. All of this is central to our humanity. We are social beings, and we should never be ashamed of needing help from each other.

After the care we have shown for one another during 2020, our sense of the primacy of the social is arguably at an all-time high. It is a good time to reflect on how we can strengthen our institutional means of protection from precarity. This involves biting the bullet on the desperately needed funding increases in key areas such as the rates of income support, the staffing levels of Services Australia, our health and education systems and, of course, the provision of public housing (all of which would also boost economic activity and employment).

Creating a strong institutional framework to protect us from precarity also means reconfiguring the current way we do things in these areas. It means reassessing whether the allocation of public funds is equitable or whether unjustifiable public support is being given to private, for-profit service-providers and systems at the expense of public and community systems. This includes areas such as aged care, the private health industry, Vocational Education And Training, private school funding, the jobactive network, and government subsidies and tax breaks that benefit sections of the housing market unrelated to public, community or even affordable, housing. The development of a social guarantee also requires a new story; one that breaks with the stigmatising and residualising frameworks of the past.