28 October 2016

By Warwick Smith

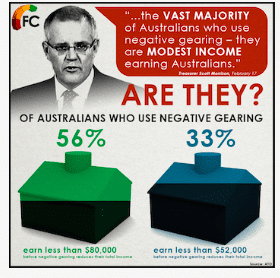

SCOTT MORRISON has suddenly announced that he cares about housing affordability. This is interesting given his strident opposition to getting rid of negative gearing and the concessional treatment of capital gains; two federal government policy settings that are broadly agreed to be major contributors to Melbourne and Sydney’s out of control house prices.

What’s Morrison’s solution? To encourage state governments to increase the supply of housing by loosening planning restrictions and releasing more land for development.

Given his opposition to the federal government using its very powerful levers to improve housing affordability, why is Scott Morrison now so keen for state governments to act? This “idea” to release more land and loosen planning regulations for new developments looks like a direct quote from developers.

Said Property Council NSW Executive Director Jane Fitzgerald on 13 October 2016:

“To continue this recovery, policymakers need to look at planning reform to make it easier for the industry to build the houses NSW needs.”

Amazing, isn’t it? Ten days after the Property Council comes out calling for planning reform Scott Morrison suddenly takes an interest in housing affordability and his solution: planning reform. Smell a rat anyone? According to the most recent data we have, the real estate sector gave the Liberal party over $1.8 million in donations in 2015 alone — and that wasn’t even an election year.

Big development companies are constantly lobbying for more land releases on the urban fringes of major cities. This is unsurprising given the profits to be made from such releases.

This “supply problem” argument makes little sense when so many of Melbourne and Sydney’s houses lie vacant due to the distorted investment environment created by federal government policy. Last year, clever water use analysis by Prosper Australia found that almost five per cent of Melbourne’s housing stock was unoccupied — or nearly twenty per cent of investor owned properties. These numbers are far higher than the official vacancy rates.

Before we rush to build more houses, we should get people living in all the houses that already exist.

The idea that we just need to free up more land for developers is far too simplistic for a complex problem like this. Sure, there’s some truth to the idea that if you could flood the market with houses then prices will come down (this is happening to some extent with apartments). However, you can’t create more land in the places where people want to live. Historically, most city fringe land releases have just converted productive agricultural land into commuter nightmares where people are forced to live because they can’t afford anywhere else.

We already know how to make housing more affordable without having to release more and more land further and further from where the jobs are.

First, we should abolish negative gearing and the concessional treatment of capital gains. These two measures combine to make asset price speculation artificially attractive. Asset price speculation is the purchase of an asset in the hope that somebody will buy it from you for a greater price — not because you improve the asset but just because assets of that type have increased in value. The difference between what you pay for it and what you sell it for is capital gain. Individuals pay capital gains tax on only half the capital gain. This is why it can make sense to lose money while you hold the property and deduct it from your personal income (that’s negative gearing) because you can more than make up for the loss with concessionally taxed capital gains.

The argument against abolishing negative gearing and the concessional treatment of capital gains is that it will reduce the incentive to build more houses. This is where land tax comes in.

We should increase the use of land value taxes and apply them to the family home. Every single tax review conducted by economists in this country has recommended the greater use of broad-based land taxes. Even Malcolm Turnbull advocated for increased use of land taxes before his “all ideas on the table” tax reform discussion disappeared into a black hole. Federal treasury analyses show that land taxes are by far the most efficient tax base available. In fact, while other taxes impose a burden on the economy, land taxes create a benefit.

Figure caption: The “marginal excess burden” of different forms of taxation in Australia. The lower the number, the more economically efficient the tax. From: Understanding the economy-wide efficiency and incidence of major Australian taxes, Australian Government Treasury.

While we increase land taxes, we should abolish stamp duties, which are among our most inefficient taxes and are a barrier to people moving to the most appropriate housing for their needs. With those things done the task of improving housing affordability is pretty much complete. If the land tax rate is sufficiently high, then it will no longer be viable to buy property and leave it empty. Not only that, it will encourage the full utilisation of land for the purpose for which it is zoned.

When you raise the prospect of higher land taxes somebody will always bring up the poor granny who lives in a million-dollar house but only has the pension for income. Of course, lifting land taxes would require measures that support low income households and those on government income support. Compensating or creating special allowances for low income households is a relatively straightforward part of any significant tax reform.

Just holding land on the basis that it will increase in value should not be a viable investment strategy. Without the market distorting combination of negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions and with market correcting land taxes, many investors will move their money to more productive destinations. This will either reduce property prices or, at the very least, reduce the growth in prices.

This is a very complicated policy area. Just doing what I outline above will definitely improve housing affordability. However, if the settings are wrong or if it’s done too suddenly or at the wrong time, it could result in a price crash. You could suddenly find that new home buyers have mortgages substantially greater than the value of their properties. The construction sector could also stall resulting in increased unemployment and a recession.

Just because it’s complicated, doesn’t mean it’s impossible or that we shouldn’t do it. It just means that it needs to be well orchestrated and carefully monitored.

The ACT is leading the way with land tax reform by slowly, over 20 years, replacing stamp duties with land taxes. This slow transition spreads the economic impact of the move and, probably more importantly, it spreads the political impact. Other states and territories should follow suit.

There’s no lack of solutions to the problem of housing affordability, it’s lack of political will to implement the solutions that’s the barrier. Easier to just give the property lobby what they want.

Warwick Smith is a research economist with progress think tank Per Capita. He tweets @RecoEco.