By Lucas Lewit-Mendes

The federal government has taken a significant step to improve the equity and sustainability of the superannuation system, by increasing the earnings tax rate on large super balances. The October 13 announcement means the changes will bring in less revenue, but they will support low-income earners and protect against liquidity issues for some high-wealth individuals.

What are the changes?

Currently, earnings during the super accumulation phase are taxed at 15 per cent, regardless of the size of the super balance. While this system is simple to administer, it is out of step with the commonly accepted progressive tax and transfer system in Australia.

The federal government’s initial policy, announced in February 2023, proposed that earnings on balances greater than $3 million would be taxed at 30 per cent instead of 15 per cent. The changes were expected to apply to around 80,000 people, or 0.5% of Australians.

Two critiques soon became prominent in the public debate.

First, the 30 per cent tax would apply to unrealised gains, i.e. paper gains, before an asset is sold. Commentators raised concerns that this would create cash flow issues for some self-managed super funds if they held illiquid assets such as property.

Second, there were concerns that the $3 million threshold was not indexed to inflation, and therefore the number of taxpayers would gradually increase due to bracket creep.

What is the new plan, and how does it stack up?

Last week, Treasurer Jim Chalmers announced a new plan, which made the following amendments from the original plan:

- The plan will be implemented from 1 July 2026 (having previously been earmarked for 1 July 2025).

- A tax rate of 40 per cent will apply to earnings on balances over $10 million. The 30 per cent tax rate will apply to earnings on balances between $3 million and $10 million.

- Both the $3 million and $10 million super balance thresholds will be indexed to inflation.

- The higher tax rates on large balances will only apply to realised capital gains. A one-third discount will continue to apply for capital gains.

- The low-income superannuation tax offset (LISTO) will be increased from $500 to $810, and the eligibility threshold will be raised from $37,000 to $45,000 from 1 July 2027.

The plan will now raise around $1.6 billion in 2028-29, the first full year of operation, compared to the original plan’s $2.5 billion. The government will also lose one year of revenue due to the delayed start, which means the new plan will raise $4.2 billion less over the next four years.

Let’s tackle these amendments one by one.

40 per cent tax rate on balances over $10 million

Around 8,000 people will face an even higher tax rate (40 per cent) for earnings on balances above $10 million. This is a sensible change to make the super tax system more progressive, but actual revenue raised may be limited if taxpayers re-allocate super into other savings vehicles such as trusts or the family home.

Indexation to Inflation

The lack of indexation was unlikely to be a serious problem in practice, as it was always inevitable that future governments would increase the $3 million threshold over time. Additionally, most other tax thresholds are not indexed, including personal income tax, although the super transfer balance cap (a maximum on contributions into tax-free retirement phase accounts) is indexed to the Consumer Price Index.

Policy certainty is an important component of the tax and transfer system, and indexing the $3 million threshold will provide security for taxpayers currently just below the threshold.

Removing the taxation of unrealised gains

The original plan – to tax unrealised gains – had two key arguments in its favour, one practical, and one economic.

First, the practical one: APRA-regulated funds do not currently split up realised gains between fund members, because assets are purchased and sold at the fund level, not the individual member level. Under the revised plan, funds will need to find a way to allocate capital earnings to each member, complicating its implementation.

Now the economic argument: as self-managed super funds (SMSFs) have control over the timing of asset sales, they can avoid capital gains tax entirely by moving an asset into a tax-free retirement account (which can hold assets worth up to the transfer balance cap of $2 million) and selling it during the retirement phase. Therefore, taxing unrealised gains as they accumulate would have protected against a huge tax minimisation loophole.

However, despite these advantages, the original plan was plagued by concerns around liquidity issues for SMSFs. While most high-wealth individuals also have high incomes and strong capacity to pay a tax on unrealised gains, some may be asset rich, cash poor. The amendment will protect those individuals.

The government could have considered an alternative model where capital gains tax accrues annually based on the account holder’s current tax rate, but is deferred until sale or death.

Overall, given the concerns around liquidity, this amendment is politically practical, and it will bring some opponents to the table to support an important reform.

Low-income superannuation tax offset (LISTO) increase

This is a straightforward and excellent amendment to help address inequality.

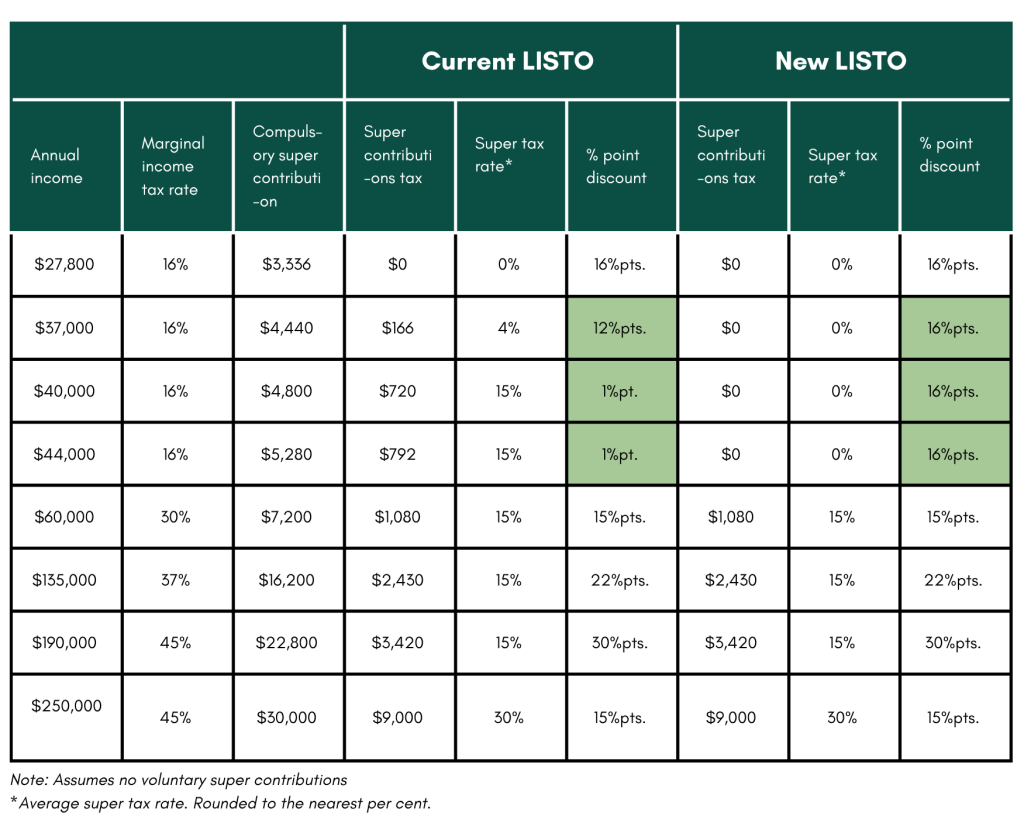

As shown below, under current arrangements, some low-income earners receive a very small discount on their pre-tax super contributions, which is an anomaly created by the stage 3 tax cuts. Under the new plan, low-income earners will receive a 16-percentage point discount, similar to most middle-income and high-income earners.

More needs to be done

Altogether, this a policy success and should be celebrated. However, more needs to be done to improve the fairness of our super tax system, which disproportionately benefits higher income earners.

1. Remove the tax-free status of retirement earnings

Tax-free retirement earnings is a poorly targeted concession. As noted above, it is also a tax minimisation loophole for SMSFs on capital gains. A 15 per cent earnings tax, in line with the accumulation phase, would raise around $5.3-7.3 billion per year.

2. Build a reform package with winners

To build a popular reform package, revenue raised could be used to reduce the high effective marginal tax rates faced by many recipients of family or welfare benefits. Taper rates exceed 50 per cent for some workers, which can result in ‘poverty traps’, where low-income workers have little ability to increase their post-tax income by working more. A suite of targeted income tax cuts would improve equity and make it more attractive for dual-income parents to both stay in the workforce.

A step in the right direction

The federal government has taken an important step towards improving the fairness of our tax and transfer system. Despite its troubled journey over the past two years, this is now a reform that is hard to refute.