The Victorian state budget revealed a government flooded with cash. Big spending on infrastructure, health, education and regional development, all while running a budget surplus, has largely been made possible by record revenue from stamp duties on housing. Thanks to record house prices and high population growth in Melbourne, stamp duty revenue is expected to rise to a record $7.1 billion.

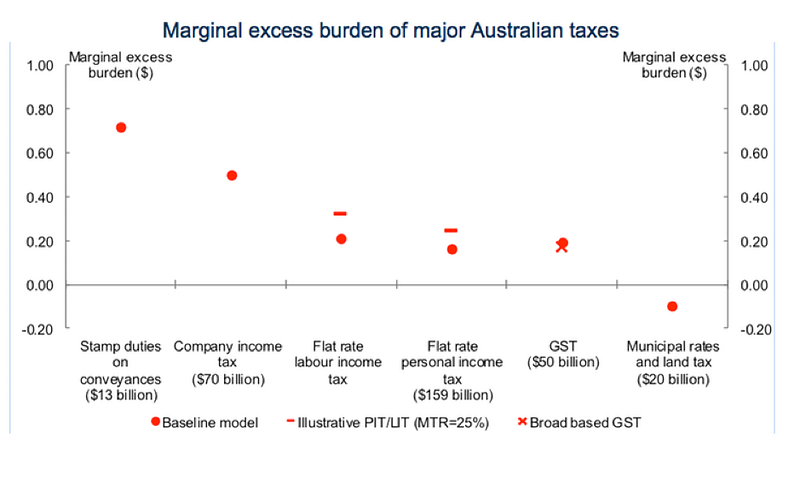

The Commonwealth Treasury department examined the efficiency of all major Australian taxes and found stamp duties to be the worst with an economic loss of over seventy cents for every dollar taxed.

One of the worst features of stamp duties is that they discourage the efficient use of our existing housing stock, because they discourage moving. People who live far from their work are much less likely to move if doing so will cost them $40,000 in stamp duty in addition to all the other expenses and hassles associated with moving. Similarly, couples whose children have left home are discouraged from moving to a smaller house by this substantial expense.

Meanwhile, The Housing Industry Association released a report that finds increasing federal taxes on housing is a bad idea, primarily because it will damage state revenues. The report includes modelling of the impact of federal Labor’s proposal to reduce capital gains tax concessions down from 50% to 25%. These changes mean that, instead of paying tax on only half the income earned from capital gains (price rises), investors would pay tax on 75% of the gains.

Yes, you heard that right, they’re complaining because they may have to pay tax on 75% of their income instead of only half. We should be so lucky eh?

So why don’t they pay tax on all of their income like the rest of us? The excuse for this generous treatment is that we need investment in housing because we need lots of houses being built. Unfortunately, the best capital gains tend to be had close to city centres, which means investors prefer to buy existing houses (as the HIA report acknowledges). This doesn’t help construction much except by lifting all prices, thus making building new houses on the outskirts of cities a bit more profitable.

In other words, our clever national solution to providing housing is to make it really expensive.

In order to defend this generous tax treatment of investors, the HIA has suddenly started crying crocodile tears about state finances, with their report warning that increasing taxes on capital gains will result in the states making much less money from stamp duties — which have provided a river of cash to state governments in recent years due to out of control house prices.

Should we let a fall in revenue from the worst tax in the country stop us from tackling housing affordability and reducing ridiculously generous taxation arrangements for housing investors? Of course not; it’s just a prompt to fix the absurd situation we’ve got ourselves into where the states are increasingly reliant on revenue from bad taxes.

Luckily, the ACT has provided us with a ready-made solution to this problem, and it sits at the opposite end of that graph above. Land taxes are the most efficient taxes in use in Australia.

The ACT government has begun a slow, 20-year transition, from stamp duties to land taxes. Every year the rate of stamp duties falls a little and the rate of land tax rises a little. This snail’s pace reform is designed to soften the one-off fall in land prices caused by the introduction of a land tax. Graduated over this time period, the impact of the land tax on prices won’t even be noticed by home owners. At the end of the 20-year period the ACT will have transitioned to a much more efficient and equitable taxation system that will benefit the entire economy.

There are a lot of reasons that economists like land taxes. You can’t hide land so you can’t avoid the tax. Millionaires can’t use Cayman Islands tax shelters to hide the two acres surrounding their mansions in Sydney and Melbourne’s most exclusive suburbs.

Land price increases are what economists call ‘economic rent’. Economic rent is unearned income. Land price rises are almost never the result of actions by the landowner, instead they are caused by collective action of the community. When the government builds a new train station in a suburb, the land value goes up substantially. Does the owner deserve that money? Similarly, population pressures, city growth and gentrification drive up land prices. The owner of the land did nothing to bring about these price rises. This is why we call it unearned income and this is why it’s the perfect target for taxation.

Taxes tend to discourage activity. As explained above, taxes on transactions (like stamp duties) discourage transactions. Taxes on tobacco discourage tobacco consumption. Taxes on labour (income taxes) discourage work. Payroll taxes discourage employment. Taxes on economic rent discourage rent-seeking. Investing in a property in order to benefit from a rise in land prices is rent-seeking; the seeking of unearned income. It should be discouraged and the fact that the government currently only taxes half of the income from this behaviour is outrageous. We should tax all of the income from land price rises and other forms of economic rent and then maybe us wage earners would be able pay tax on only half of our income.

Now there’s tax reform the public could get behind.