Introduction

On 9 December 2020, the Australian Government introduced the Fair Work Act (Supporting Australia’s Jobs and Economic Recovery) Bill into the Australian Parliament. The Bill is expected to come to a vote in the Senate in early March 2021. According to the Government, its Industrial Relations (IR) ‘reforms’ are the result of a period of ‘consultation’ between business leaders and the Australian union movement, and “…will give businesses the confidence to get back to growing and creating jobs, as well as the tools to help employers and employees to work together in a post-COVID Australia”.

Sounds good, doesn’t it? The problem is that the Bill contains virtually no measures agreed to by the Australian union movement on behalf of workers during those ‘consultations’ but is rather a big-business wish-list of changes to the Fair Work Act that will further weaken protections for Australian workers and give more power to big employers to hold down wages and increase job insecurity.

Download the briefing note

The Government claims that ‘more flexibility’ is needed for employers to create new jobs and get Australians back to work. They say that businesses that were ‘hit hard’ during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and economic shut-down need to have our workplace rules relaxed so they can hire more workers and return to profitability.

This isn’t true. Big employers in Australia already have far more power to dictate the rights and wages of their workers than at any time in the last century. For years before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Australian workers had some of the highest rates of insecure and casual work in the developed world and had gone for the better part of a decade without a real wage rise.

The pandemic showed us just how damaging job insecurity is, not only to individual workers and their families, but to society as a whole. Workers in some of the most essential jobs during the health crisis, such as aged care, food services and quarantine security, were those most likely to contract and spread the virus. This was not because they were irresponsible, but because they couldn’t afford to stay home from work when they were sick, and often had to work two or three jobs to make ends meet, taking the virus with them between multiple workplaces.

At the same time, many people reliant on casual and part-time work saw their incomes collapse as shifts dried up. Many remain reliant on JobKeeper and the increased rate of JobSeeker to make ends meet. Household consumption, while recovering, remains depressed and spending will almost certainly fall further when thousands of workers find themselves without essential income support after 28 March 2021.

In a recent submission to the Senate Inquiry into the Bill, 23 leading labour law academics condemned the Bill as “a deeply flawed initiative” that “will not just fail to address pressing labour market issues such as wage stagnation, insecurity of work and entrenched inequalities, [but] will exacerbate them”.

The fact is, this Bill is a recipe for growing inequality and slowing Australia’s economic recovery. It’s the opposite of what we need right now. We have submitted to the Senate’s Inquiry into the Bill and will be testifying at the upcoming hearing to argue against it. To make the contents of the Bill more accessible to the regular people whose work it will impact, we’ve also prepared a Per Capita Briefing Note that lays out the Bill’s provisions and our arguments against them clearly and concisely. You can download the briefing note below.

Download the briefing note

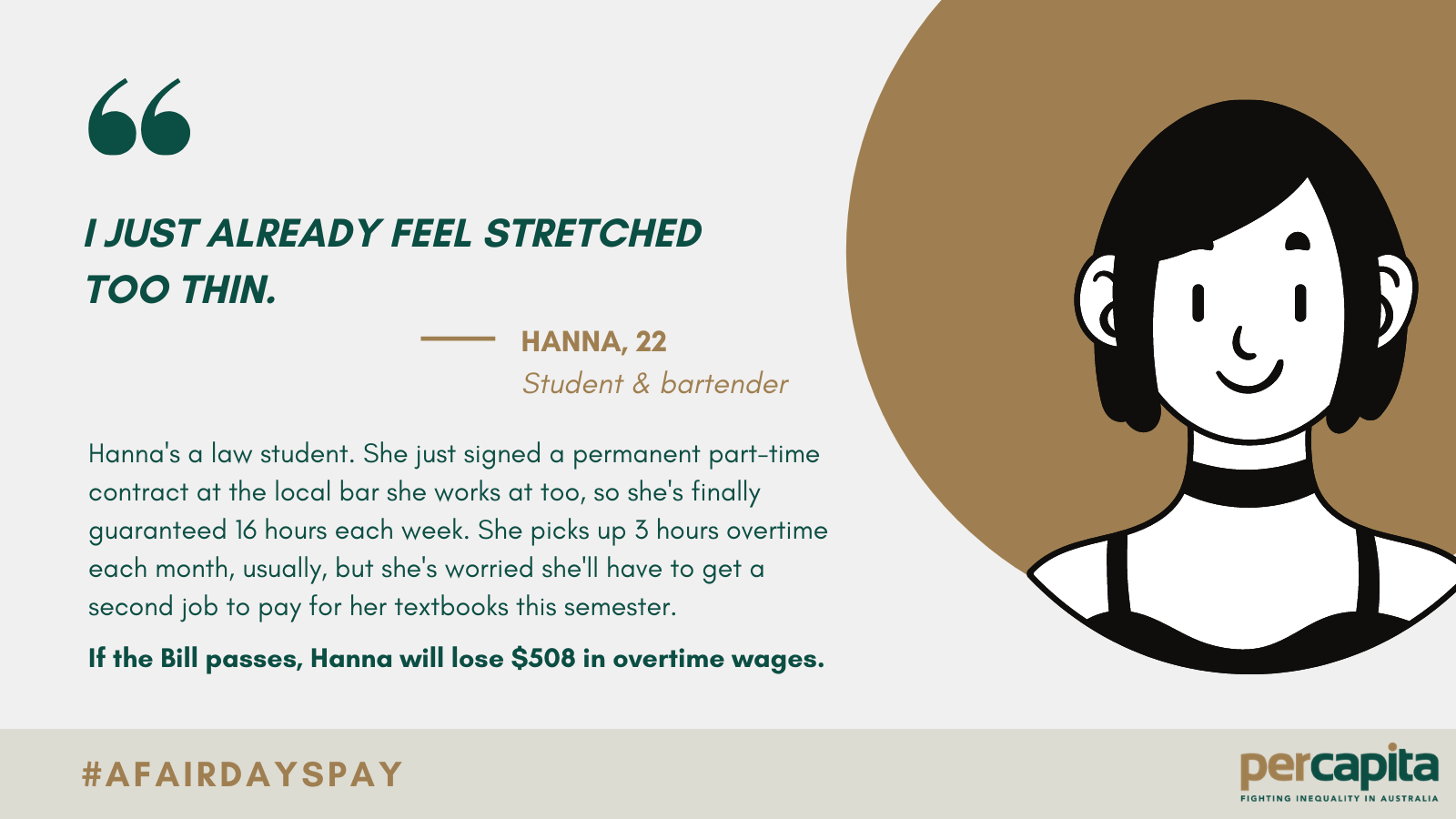

We’ve also prepared a series of six case studies to illustrate how passing this Bill would affect different examples of workers. NB the first two case studies – Hannah and Helena – apply in a situation where the first of two policy options canvassed in the Bill for allowing employers to avoid paying overtime passes. This first option is the Government’s preferred option and would allow employers in the hospitality and retail sectors to be able to offer additional hours to part-time workers without paying overtime.

The next four case studies – Barry, Yusef, Julie, and Tranh – apply in a situation where the second option passes: the creation of a new employment category knowns as ‘flexible part-time’. As opposed to the first option, which applies only to awards that cover workers in retail and hospitality, this new employment category would be inserted into all modern awards, covering all types of work. This would allow employers to hire employees with pro-rata leave entitlements, like permanent part-time workers, but to roster them on to work only when the business needed their labour, like casual workers.