By David Hetherington

The ideas landscape in 2012 was marked by the re-emergence of a dormant historical giant – inequality.

Through the boom years, inequality was treated as a necessary cost of growth, inconvenient but unavoidable, and since the crisis, it has been mostly incidental to the bigger problem of kick-starting growth.

Yet in the last 12 months, inequality has made a comeback. Why now? And why has the comeback missed Australia?

To trace this development, we must return to the latter part of 2011 when the Occupy movement sprung up in New York. In one sense, this was yet another manifestation of leftist protest politics. But unlike most protests, it made the Establishment sit up and take notice.

Last January, Martin Wolf, perhaps the world’s foremost economic commentator, identified inequality as one of capitalism’s great challenges as part of the Financial Time’s “Capitalism in crisis” series. In September, The Economist magazine devoted a 16-page special to the politics of inequality. These are hardly bleeding-heart journals.

The politics of inequality are complex. First, the form of inequality has changed markedly in the last generation. Global inequality has fallen considerably, driven by the exit from poverty of 400 million people in China, but also by rapid growth in large emerging economies like Brazil, Indonesia and Mexico.

Contrary to popular belief, income inequality has fallen in some developed countries too, at least under the conventional Gini measure and at least until 2007. This fact seems to contradict the popular meme of the much-maligned “One Per cent”, but both stories are true. In the developed economies prior to the GFC, incomes grew strongly in the poorest households and for middle-income earners, even as earnings for the super-rich raced away.

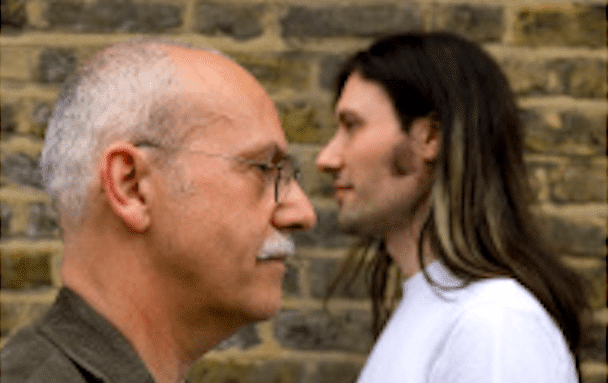

While the rise of the super-rich raises legitimate concerns over political influence, the One Per cent debate also masks the real inequality story of our time: the growing gap between young and old.

The rich-country response to the GFC has been to protect incumbent interests, predominantly the baby boomers and their kids. They are the shareholders of the exposed European banks, the beneficiaries of the sacred US Medicare program, the owners of the defined benefit pensions.

Conversely, the pain of the GFC has fallen disproportionately on the young. It is the young who are not being hired, as employers embrace hiring freezes. In Britain, the youth unemployment rate is 20 per cent, in France it is 25 per cent, and in Spain a gut-wrenching 54 per cent. Even allowing for some black market employment, these figures are horrifyingly high. Entire classes of school and college leavers are on the dole. Studies in America and Britain have found that youth unemployment leaves a ‘wage scar’: someone who experiences a year’s unemployment when young sees a wage rate 23 per cent lower 10 years later than a peer who was not unemployed.

The crisis has hurt the young in other ways. Spending cuts have fallen on education which crimps long-term employment (and growth) prospects, and community services which support vulnerable youth.

And perhaps most daunting is the debt burden, public and private, that’s being passed down which today’s young workers and their children will have to pay off. Economists expect this to suppress economic growth for a generation or more. There’s a real likelihood kids in the West will be worse off than their parents for the first time since the Dark Ages.

In Australia, we are blissfully removed from the global inequality debate, and its implications for the young. Inequality here is treated as a problem largely solved. The Australian’s commentator Judith Sloan wrote recently (pay-walled) that it is absolute, not relative, poverty we should concern ourselves with and by that measure, she argued, Australia is doing pretty well.

So why should Australia worry about inequality given our evident prosperity? For a start, entrenched poverty still exists in significant pockets. Research by ACOSS has found that 2.3 million people, including 575,000 children, were living below the poverty line ($358/week) in 2010.

More worryingly, the same structural changes that have exacerbated poverty in Europe and North America are coming down the line at us. Our debt may not be as large, but our governments are increasingly straitened, forced into spending cuts as tax revenues stall. Federal and state governments alike are at a loss on how to pay for critical investments in education, infrastructure, disability and aged care. Our biggest states are actively taking the knife to spending on schools and vocational training.

The problem is that these investments are needed to drive Australia’s future prosperity. If we can’t make them now, our kids will struggle to thrive in an ever more competitive global economy while the political dynamics will dictate that ever more support is directed to older generations.

The fact is government revenues are simply too low to fund the kind of society we expect AND the rising costs of the baby boomers. If it comes down to that contest, baby boom needs will win. So the tax-to-GDP ratio simply must rise.

Young people feel increasingly disenfranchised from mainstream politics and in places like Europe, their sense of inequality is turning to anger. If Australia cannot successfully navigate the end of the mining boom and if we don’t invest more in our young people, this sense of inequality will take root here too.