Cory Bernardi is perhaps best thought of as the Liberal dog that barked. While his views may be too extreme for the rest of his party to openly embrace, they tell us that behind the Liberal fence some intriguing psychological and tactical changes are going on.

Let’s start with psychology. The title of Bernardi’s latest book, The Conservative Revolution, is revealing in an unintended way: it is a textbook example of George Orwell’s term “doublethink”. Bernardi is asking us to hold two totally contradictory thoughts in our heads simultaneously: that he is at once a conservative and a revolutionary. As the philosopher Edmund Burke, whom Bernardi regularly quotes out of his historical context, tells us, you can’t be both a conservative and a revolutionary, which means there’s a fundamental dishonesty at work here.

So, Senator, which are you?

It’s obvious why Bernardi would want to identify as a conservative. It’s a term the political right all but owns – even though in Australia’s case conserving the past might actually mean something more left-wing than Bernardi has in mind. It is, however, Bernardi’s self-identification as a revolutionary that is most curious.

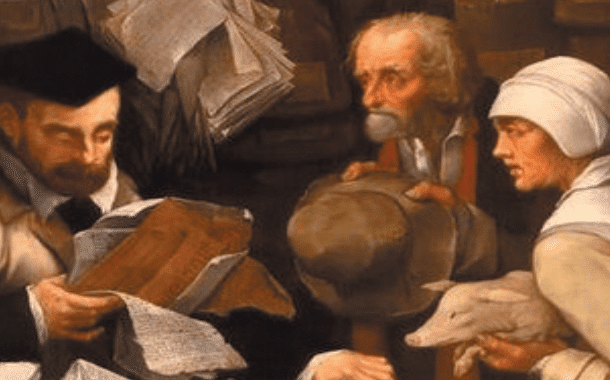

Bernardi, in fact, seems obsessed with the idea of revolution – which he defines in moral rather than political or economic terms, and which with its emphasis on “Faith, Family, Flag and Free Enterprise” comes across as the modern equivalent of the bonfire of the vanities. Catechism-like, he repeats the words “this is why we need a conservative revolution” no fewer than 35 times throughout the book. I suspect Burke would see him not as a true conservative but as the reincarnation of the 15th century Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola.

This all points to one of the big underlying developments of contemporary Australian politics: after a century of what we can roughly describe as a social democratic society, it’s the left that often wants to defend the status quo and the right that wants to rip it up. As Bernardi’s revolutionary obsession demonstrates, it is the right, not the left, that has inherited the revolutionary psychology usually associated with Marxism.

This has been going on for some time. PP McGuinness, Peter Coleman, Keith Windschuttle: all started on the Marxist left but ended up on the anti-Labor right.

But while they dropped their youthful leftist belief in economic equality, they maintained their youthful fixation with concepts such as class, cultural power and revolutionary change. Think of the concept “new class elite”, which informs so much of Bernardi’s book – it is pure inverted Marxism. There are others, too. Consider Kevin Donnelly, whom Christopher Pyne has just appointed to review the national curriculum. Donnelly very literally conceptualises his task in direct and vivid Maoist terms – as countering ““the cultural left’s long march through the education system”.

The dog that didn’t bark

Bernardi’s new book also tells us much about the right’s tactical approach to the electorate. His well-publicised socially divisive stances on issues like Islam, gay rights and the traditional family may be too hot or too cranky for his colleagues to endorse (publicly, at least) but they are the inevitable product of a party that sees electoral politics primarily as a competition for the emotional allegiance of voters, and which isn’t afraid to resort to fear and resentment to achieve its ends.

Bernardi is little more than an irritant for the Liberal Party. The real danger lies in the possibility that Bernardi’s rhetoric might be taken up by the rank and file and forced on a reluctant parliamentary leadership, as the Tea Party’s rhetoric has managed to do in the US Republican Party.

The existence in the Liberal Party of someone like Cory Bernardi raises another interesting point: why is there no one in the contemporary Labor Party who can be considered a lightning rod for a radical critique of society?

If Cory Bernardi is the dog that barked, the absence of a comparable ideological rabble-rouser on the Labor side may constitute the dog that didn’t bark. The disappearance from the ALP of radical thinkers, even nutcases and cranks such as Bernardi – once so commonplace – perhaps denotes a party that has become too technocratic and cautious in its approach and too monolithic and unadventurous for its own good.