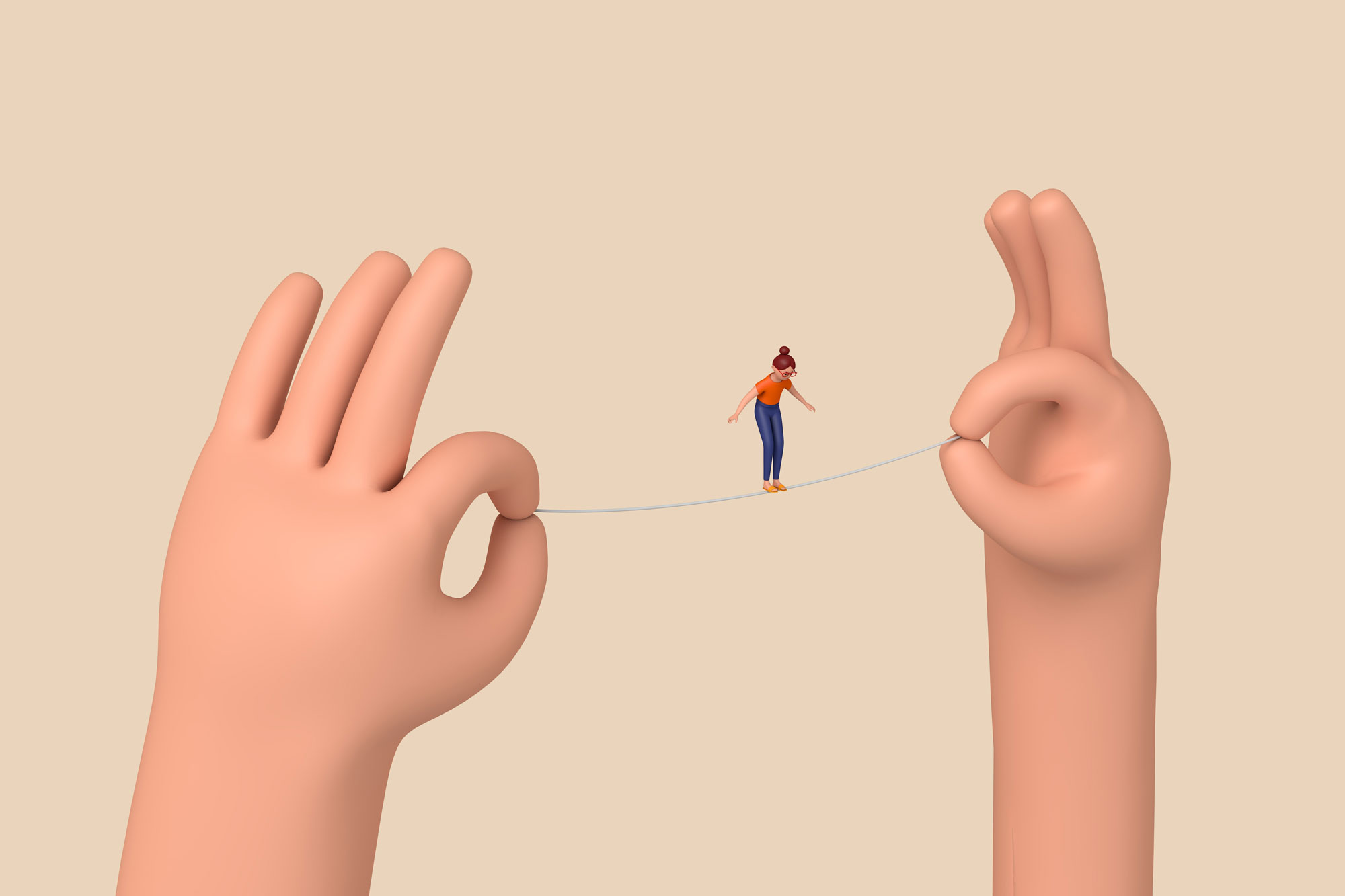

Emma, Juanita and Suzanne have one thing in common: they’re on a high-wire with no safety net.

Juanita McLaren apologises, declaring through tears that she’s usually the most cheerful person in the room. To her left are two women who are also on stage to discuss what it’s like raising a child as a single mum in Australia. “I’m sorry,” she repeats. “This is just really depressing.”

“I’ve done everything right,” Juanita tells the crowd, who have gathered to hear the key findings from the Council of Single Mothers and their Children’s latest national survey. “I fought for my kids, I volunteered, I’ve spoken at the United Nations on behalf of single mothers. I have two degrees, I’ve got a Masters. A Masters took me five and a half years to get but it promised a 40 percent increase in income,” she says. “And I could do it while my three sons were in school.”

It didn’t work out that way though. That beefed up salary also never eventuated. Single parenting meant her resume was impressive but patchy and stable long-term work was hard to find because it meant turning down immediate paid opportunities to wait for something more lucrative. Juanita has $49,000 in superannuation, and a $40,000 HECS debt. This is the point when her tears start to flow.

Almost all of her money goes to her rent, she says, and her eldest son pays $450 a month which he earns in his apprenticeship. Juanita is grateful to him, but she hates that a 19 year old has to worry about taking care of his two little brothers. “If 30 percent [of your wage is considered] housing stress, I don’t know what 85-90 percent is,” she finishes. The room is silent.

The event’s host, FW’s deputy managing director Jamila Rizvi, notes that we’re all used to seeing stories of inequality like this distilled into statistics: one in five, one in ten, one in three. Numbers may be shocking but they don’t have names. But today, they do. On the Council’s panel are three women: Emma Dawson, Juanita McLaren and Suzanne Baker.

Emma Dawson is an economist and the Executive Director of Per Capita, meaning she is among the 77.7 percent of single mothers who are employed, according to the survey. Another eight percent are actively looking for work. “So this idea, this mentality that has dominated our conversation, our national policy settings for so long, that single mothers don’t want to work is rubbish,” she says.

“I’m now seen as a risk even though I was the breadwinner in our family for the last five years.”

At the start of the year Emma’s husband died after a long illness. She shares that although he was sick, hadn’t worked for a long time, and their mortgage was calculated entirely on her salary, she was told she would need to reapply for it after he died if she wanted to access redraw.

“I’m now seen as a risk even though I was the breadwinner in our family for the last five years.”

Both Juanita and Suzanne share times they’ve had enough money for a house deposit but couldn’t find a bank willing to lend to them. For Suzanne, housing is the single biggest issue facing single parent families. Her daughter is 17, and in her short life the two have moved 17 times. Suzanne estimates the cost of moving once a year over almost two decades adds up to about $15,000. They have only ever been accepted for properties no one else applied for.

“It’s not just about affording the rent,” she says steadily. “It’s a demoralising, stressful, exhausting and all consuming job looking for a rental property.” Suzanne is on a public housing waitlist but is told the wait will be at least ten years, if she’s successful.

Right now Suzanne considers herself lucky: she lives in a property close to her daughter’s school where her rent is below market rate. The trade off is that it doesn’t meet rental standards, and that Suzanne has to carry out maintenance and repairs herself. She is already dreading what they will do next year when they’ll have to re-enter a tight and increasingly expensive rental market because her landlord’s daughter is moving back in.

More than half of all single mothers in Australia live below the poverty line, despite the fact that almost eight out of ten are in paid employment.

According to the Council’s survey, 87 percent of single mothers are concerned about their financial wellbeing – and with good reason. Single mothers most frequently earn between $20,000-$40,000 a year (30.2 percent) followed by $40,000-$60,000 a year (22 percent). Another 6.7 percent earn below $20,000 a year, meaning more than half of all single mothers in Australia live below the poverty line, despite the fact that almost eight out of ten are in paid employment.

In addition to this, 34 percent have no savings, 67 percent have experienced family violence, 48 percent have been involved with Family Law and just under 40 percent of that group paid for their own legal representation. These statistics, when viewed as parts of a whole, paint the picture of a system that disadvantages single mothers from start to end.

All three panellists agree that change is coming, but that it’s not fast enough and not at the scale or in the areas required. The most significant improvements included increasing the cut-off age for the Single Parenting Payment until the youngest child is fourteen years of age instead of eight; the abolition of the punitive Parents Next program; and amendments to the Family Law Act that put a greater emphasis on the safety and best interests of the child over the need for shared parenting – an important distinction in cases of domestic and family violence.

They each identify areas where more needs to be done, including addressing insecure housing and building more public housing, as well as amending marginal tax rates to stop disincentivising single mothers who fear taking on more hours because they might lose access to their healthcare card or parenting payment if they earn too much in a short period.

“We have structured our economy in a way that regards women and their work as things that are done for love,” says Emma. “Unpaid care work, the burden of domestic role is carried by women. And so if we have structured our economy in that way, and we have, then we are responsible for those we have marginalised and for the structures that marginalise them.”

In her opening remarks, Jamila describes single motherhood as a complex juggling act, a high-wire performance with an insufficient government safety net. The truth is that the high-wire tightrope act is becoming increasingly dangerous. We can no longer sit back and watch – it’s time for the circus to end.

Originally published by Sally Spicer – FW’s Communications Director – on the Future Women blog on 27 Nov 2023. She was raised by an excellent single mum named Kim, who taught her everything she knows.