By David Hetherington

2 April 2015

The U2 song Desire is possibly the only number one single that references a branch of economic thinking. “Voodoo economics”, chants the song’s overdub, borrowing the derisive label that George Bush Snr coined for Ronald Reagan’s economic policy.

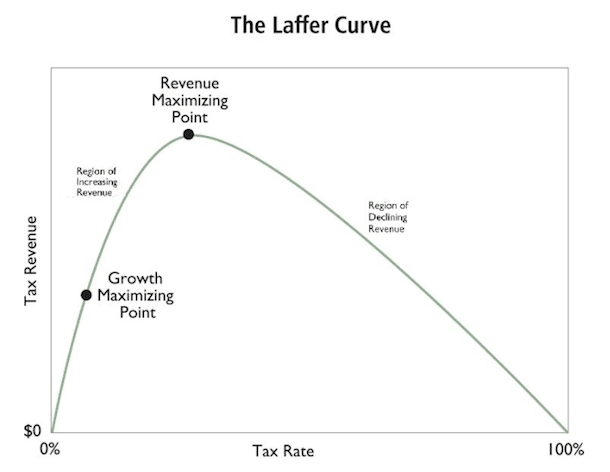

Forty-five years on, voodoo economics is back in the spotlight with the visit to Australia of one of its chief shamans, Arthur Laffer. Laffer is most famous for his eponymous curve, which purports to show that cutting taxes on the rich raises extra tax revenue.

Why did Bush, no bleeding-heart leftie himself, describe these neoliberal economic nostrums as voodoo? He recognised that they ask you to suspend belief, to discard reason, and place your faith in arguments that run counter to common sense. There is a proud tradition of such nonsensical arguments. Just as reducing taxes on the wealthy raises more revenue, so cutting public spending in a downturn helps the economy. And lowering minimum wages is good for workers. And public services can be maintained in the face of regular tax cuts. In each case, the logic is completely counterintuitive but we are asked to take such truths of supply-side economics as self-evident.

Unfortunately, these self-evident truths don’t stack up so well when confronted with reality. Reagan put the Laffer approach to the test across his two terms in office. He cut the top marginal tax rate from 70% to 31%, while the average tax rate for the top one percent of earners fell from over 40% in 1980 to 25% by 1990. Yet between Reagan’s election in 1980 and his departure from office in 1989, the federal government’s tax revenues as a share of GDP fell from 19.0% to 18.4%.

Even amongst those economists who accept the Laffer curve theory, the consensus is that cutting tax would only raise revenue if average tax rates are in the region of 70%, far higher than conceivable in any developed economy today. The policy implication for modern economies is that more revenue would be raised by lifting taxes from current levels, rather than reducing them. Funny that.

Other supply-side theories similarly struggle when tested in the furnace of reality. In a famous study of fast-food restaurants, American economists David Card and Alan Krueger found that an rise in the minimum wage in New Jersey actually increased employment of low-wage workers compared with neighbouring Pennsylvania where the minimum wage stayed unchanged.

On one level, it’s remarkable that theories with such poor empirical track records generate such attention. In Australia, Laffer will be flown around and feted at dinners across the country as a guest of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Institute of Public Affairs and the Sydney Institute.

On another level, though, this is perfectly understandable. For these theories, and their associated branding , are triumphs of marketing over reason. Laffer’s curve, Eugene Fama’s “efficient markets hypothesis”, the Black-Scholes model for options pricing – all have becomes brands to be celebrated in spite of deep empirical failings. (Fama’s hypothesis implies financial bubbles don’t exist; Scholes’ application of his theory led to a $4 billion hedge fund collapse.)

Yet they have been packaged as glamorous theories to be marketed and celebrated. Why? Because it suits wealthy vested interests to defend their positions with a patina of economic respectability. Empirical outcomes are neither here nor there. If you can convince enough influential policymakers and commentators, as Reagan was convinced by the Laffer curve, you can shift the distribution of wealth and income in your favour. But as with so much in today’s society, you need exceptional packaging and marketing to pull it off. Hence the cult of personality around the celebrity economists

The celebrity economist is a relatively new phenomenon, which parallels the rise of neoliberalism over the last three decades. In the 1950s, the Kiwi economist William Phillips drew a famous curve of his own showing a trade-off between unemployment and inflation, yet didn’t get the rock-star treatment enjoyed by his supply-side successors. But then his argument didn’t lead to policies that further concentrate income and wealth. So it probably wasn’t worth the marketing investment.