As the Turnbull Government pushes hard to secure the votes needed to pass its company tax cut for large corporations, minor party senators would do well to heed the actions of big business when it comes to local investment and wage increases for workers, rather than listening to their well-crafted words.

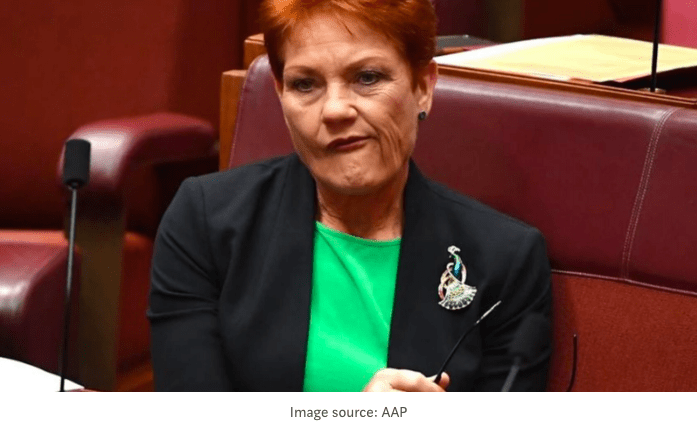

On Tuesday, Pauline Hanson declared she was considering reversing her opposition to extending the cut to companies with a turnover of more than $50million a year, saying she had visited the Pilbara to talk to mining companies, and been told that they “want to invest in Australia”.

And on Wednesday, Steve Martin, who replaced Jacqui Lambie in the Senate last month, was apparently persuaded that supporting the tax cut would achieve his goal of “strengthening Tasmania’s global export markets, bolstering jobs creation, wages growth and building sustainable communities”.

So far, it looks like Matthias Cormann’s temporary engagement of former Minerals Council chief executive Brendan Pearson as an adviser in his office to sell the case for tax cuts directly in internal senate negotiations is paying off for the business lobby.

It’s a shame the average Australian worker can’t fly cross-bench senators around the nation to argue their case for fairness, or leave their jobs to work short-term for a minister and gain such privileged access to the negotiations at the heart of government.

If they could, they would almost certainly tell the cross-bench not to support the tax cut: Per Capita’s annual tax survey last year found that, for large corporations with a turnover in excess of $50million annually, public support for the tax cut is just 17% and fully three quarters of Australians oppose the cut outright.

The fact is, despite business’s vociferous protestations that a tax cut will lead to greater local investment and a better deal for workers, none of their recent behaviour indicates any such thing.

There is a fundamental mismatch between what business says it will do with increased profits, and what actually happens when extra money flows into their coffers.

Moreover, there is a real discord between the fiscal and monetary policy settings of the Australian economy and the behaviour of business — one which is directly responsible for weak wage growth and low investment in the Australian economy.

Per Capita’s recent report, The Future of the Fair Go: securing shared prosperity for Australian workers, explains this divergence in detail.

Over the decade since the Global Financial Crisis, business has exacerbated wage weakness through its preference for cost reduction over investment spending.

Mining investment peaked at around 9 per cent of GDP in 2012 and has since fallen rapidly to below 4 per cent of GDP. Non-mining investment has been in steady decline from above 12 per cent in 2005, to around 9 per cent today.

The mining boom effectively masked the fall in the investment share of the rest of the economy and as it has abated, total private investment has fallen from around 17.5 per cent to 12.5 per cent in just five years.

Why has this happened? As RBA Deputy Governor Guy Debelle stated last year, there are “indications that the stock market is rewarding cost reduction rather than investment spending where the payoffs are multi-year rather than immediate”.

In other words, business leaders pursue short-term profits and returns to shareholders over long-term investment because that’s what the stock market wants — and their own remuneration and share holdings are reliant on share market performance.

Dividend pay-out ratios in Australia have grown from around 60 per cent of profits throughout the 2000s to around 70 per cent since 2010, with a peak of over 80 per cent in 2015.

This mirrors a global trend in which firms are preferring to return cash to shareholders rather than invest in growth activities. In fact, a recent report from the US noted that, when surveyed, 80 percent of CEOs said they’d “pass up making an investment that would fuel a decade’s worth of innovation if it meant they’d miss a quarter of earnings results”.

So much for wanting to invest.

And what’s the impact on jobs and wage growth of this short-term, profit-driven mind-set? As businesses have sought to maximise cash returns through cost-cutting, they have reduced their demand for labour.

In Australia, this effect has not been seen in the top-line employment numbers, but in underemployment, underutilisation and wage weakness. Firms have deliberately used both volume and price levers to manage their labour bill downwards.

Let’s make this divergence between policymakers and business behaviour clear.

In June last year, Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe acknowledged that “[t]he crisis is really in real wage growth,” and called on workers to demand a pay rise.

At the same time, the 2017–2018 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) updated Treasury’s forecasts for wages to increase by 2.25 per cent through the year to the June quarter 2018 and 2.75 per cent through the year to the June quarter 2019. (Note that the forecast return to budget surplus relies on these wage increases, which are simply unrealistic based on current trends).

Yet despite these expectations from policymakers, business is not coming to the party.

The Australian Industry Group’s Business Prospects Report, released on 24 January, explicitly calls for “[t]he continuation of moderate wages growth”, saying that “[t]he record jobs growth of 2017 and the ability to meet expectations of still higher jobs growth in 2018 are closely associated with the moderate wages outcomes of recent years and require the continuation of this pattern into 2018”.

In other words, business has no intention of granting wage increases to workers — they have said so clearly, as recently as January.

There is simply no evidence, based on current behaviour, that a tax cut would be passed through to workers, no matter what the silver-tongues in the business lobby tell Hanson and her fellow cross benchers.

As the AIG’s own report makes clear, business leaders regard weak wage growth as an essential factor in their increased profitability and growth, the results of which they will, on all behavioural evidence, continue to return to shareholders in increased dividends, and to themselves in grossly excessive executive remuneration.

When viewed in combination with ongoing attacks on workers’ ability to organise and bargain collectively for wage growth and decent working conditions, it is clear that it is largely the behaviour of industry and big business, abetted by free-market cheerleaders in government, that is to blame for the breakdown in the social contract that has underpinned Australia’s egalitarian society for over a century.

Cross-bench senators from minor parties might want to think twice about becoming complicit in that; after all, many of them were elected on a platform of standing up for the battler against the big end of town.

Providing a $65billion windfall to big business, with nothing but a promise that they will share the spoils, would indicate they have been seduced by the same forces of greed and power that have led to Australia having one of the most precarious workforces, and highest rates of underemployment, in the OECD.

The election results in Batman and South Australia on the weekend showed that minor parties can’t take their support for granted. Standing up against a tax cut that will likely do little for the wellbeing of everyday Australians should be a no brainer.

Emma Dawson is Executive Director of Per Capita. She tweets @DawsonEJ.